|

PageBox |

| Support | Map |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Software and business method patents - Patent analysis

When I analyze a competitor patent I do two things:

I assess the risk that a program of my company infringes this patent, which is also legal work

I assess the innovation disclosed by the patent.

It is important to keep the assessment of the infringement risk and the innovation assessment separated. It may look obvious to some readers but in real life when you understand the matter this is tough to not be influenced by your opinion. You tend to overlook patents that do not teach you anything you do not know already. You have to repeat yourself that:

The role of a patent examiner is not to assess innovation but to determine (1) if a patent application meets patent criteria defined in a manual (2) if the method or system of the patent application is already described in a set of databases.

The role of courts is to determine (1) the patent validity and scope (2) the facts that the jury will use to render the verdict.

The role of juries is to determine if the defendant uses the process or method claimed in the plaintiff patent.

Today to get a legally-strong patent an applicant only needs to describe on time a combination of known processes and methods, novel and useful because of an environment change like the Web or a new regulation. We can understand that the Constitution sentence: "Congress shall have power ... to promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries." means "Congress secures an exclusive right on their discoveries to the inventors because these discoveries represent a progress in science or useful arts." However the patent system is gently moving away from this utilitarian model toward a proprietarian model as shown in the thesis of Nari Lee. I believe that the reasons for this evolution are simple:

Patent offices and lawyers live in a commercial world. Nolens volens they have to deliver the patents that their customers want.

Customers have changed. In 18th and 19th century the applicant was a person. Since the beginning of 20th century the applicant is usually a corporation. Before WWII only research centers were patenting. Now patenting is a part of the development process. The question tends to no longer be to secure exceptional findings due to chance and combination of talents but to protect the Intellectual Property of a company, this Intellectual Property being a development deliverable in the same way as the product and the documentation. Therefore customers are pushing for the proprietarian model.

Today the vast majority of the software and business method patents are "proprietarian" patents that hardly represent a progress in science or useful art. The MercExchange patents, which are examples of "proprietarian" patents, show the downside of the "proprietarian" model. The money spared by companies in identifying inventions (almost any development can be patented) is more than counterbalanced by penalties and extra burden on development (monitoring of the infringement risk) and legal work (lawsuits, settlements).

The debate about proprietarian versus utilitarian Intellectual Property is not new. Jefferson wrote: "Stable ownership is the gift of social law, and is given late in the progress of society. It would be curious then, if an idea, the fugitive fermentation of an individual brain, could, of natural right, be claimed in exclusive and stable property. If nature has made any one thing less susceptible than all others of exclusive property, it is the action of the thinking power called an idea, which an individual may exclusively possess as long as he keeps it to himself; but the moment it is divulged, it forces itself into the possession of every one, and the receiver cannot dispossess himself of it. Its peculiar character, too, is that no one possesses the less, because every other possesses the whole of it. He who receives an idea from me, receives instruction himself without lessening mine; as he who lights his taper at mine, receives light without darkening me. That ideas should freely spread from one to another over the globe, for the moral and mutual instruction of man, and improvement of his condition, seems to have been peculiarly and benevolently designed by nature, when she made them, like fire, expansible over all space, without lessening their density in any point, and like the air in which we breathe, move, and have our physical being, incapable of confinement or exclusive appropriation. Inventions then cannot, in nature, be a subject of property. Society may give an exclusive right to the profits arising from them, as an encouragement to men to pursue ideas which may produce utility, but this may or may not be done, according to the will and convenience of the society, without claim or complaint from any body."

So the original rejection of the proprietarian model was inspired by philosophy. An unfortunate consequence of this choice is that the drawbacks of the proprietarian model were never made apparent.

Turning back to innovation assessment I would like to explain

What is its target

Why this assessment is useful

How I proceed

How innovation assessment techniques could be used to improve the patent process

The innovation assessment targets patents and public patent applications filed by other companies and organizations. The target must be adapted to the resources and to the ambitions of the top management. An innovation assessment takes one week and more. One person may realistically assess thirty patents per year and even less if she has other tasks. So this is important to reduce the scope and to eliminate as many patents as possible through a shorter patent analysis. This scope should be consistent with the scope monitored with other means like traditional business intelligence and web site monitoring.

The main objective of the patent analysis is to acquire an understanding of the patent or patent application sufficient to talk about it and get feedback. However the patent analysis is useful in another way. This is one of the best business intelligence means. A patent or patent application teaches you the technical choices of the competitors and the constraints they have to manage. Combined with financial reports (10K forms), Web sites and press releases patents even allow to guess organization charts. My experience is that the patent analysis takes at least one day and substantially more when the patent or patent application discloses interesting data.

We need innovation assessment to

identify the strong points of a competitor

predict in which areas they will grow

identify the areas in which the patent or patent application may hinder the development of our company

When we conclude from the patent analysis that a patent or patent application may contain a valuable innovation or represent a particular threat we try to find the competitor product that implements the patented process or method and we check if and how the company reported this innovation to stock holders.

Before discussing how I proceed to assess the innovation in a patent I must introduce some ideas and concepts. First an invention is always a combination of old inventions. It may look obvious if you think that an invention always leverages on an existing environment but this is also true in another and more important way. We invent using a bank of old inventions much in the same way as we speak using a bank of words, just because our brain is designed to work in that way and not in another way. Furthermore we do not try combinations of old inventions randomly. We associate old inventions in a way that conforms to some production rules. I believe that a person is a good inventor, not because he knows more old inventions than others or superior capabilities to combine old inventions but because he has a more sophisticated representation of the old inventions he knows and better links or bridges between these inventions. If your work consists in designing or creating you probably noticed that:

You do not have so often "flashes of genius".

When you have such flashes the idea usually turns to be impractical.

When you did something big you do not necessarily remember a moment where you had an inspiration. With the time I came to the conclusion that "flashes of genius" are frequently signs of lack of concentration: if you are focused on your task you do not pay attention to what happens to you.

You have more often these "epiphanies", when something you have learnt suddenly makes sense. For me an epiphany is just the moment an enumerable list of recipes becomes a set of nodes connected to each other and to pre-existing knowledge. The nodes themselves are more complex than recipes and they can attract or push back other nodes.

You may find that "old invention" is probably not the way to name what the inventor knows. We do not call old invention what we use every day. But nobody describes an old invention in the way his inventor would have described it. Writers frequently say that once they achieve commercial success their books do not belong anymore to them (metaphorically - authors have reproduction rights.) If you are programmer you may have experienced the same thing. If your program works and addresses the customer need, after a couple of days people start using it in ways you never imagined and they talk about it in a way different of your way. Something in the program exists on its own. Even if the program is rewritten many times this thing will remain. So, as a contribution to the progress of science and useful arts, an invention is better defined by people who use it than by people who invented it. Therefore inventions relate more to perception (and later knowledge) than to performance and we can rightfully say that knowledge is made of natural laws, other abstract stuff and "old inventions".

To further clarify the issue I would like to give an example. In 1994 I attended a meeting with a customer. Just before the meeting a system engineer told me that he wanted to show me something of interest. The thing was the first browser I ever see, Mosaic. For me the nuts and bolts of the Web were apparent: I was using Internet. I was writing client/server and X programs. For me interpreting a message to display a corresponding image was known art. I found some choices surprising. For instance why this HTTP protocol and not the simpler FTP or a really sophisticated protocol if needed? I also found HTML too verbose. Later on I met people of Airbus who were extensively using SGML. I realized that for these people HTML was SGML for dummies. So I had doubts but I agreed that the browser was an invention because its inventors choose a correct combination of old inventions and made the right compromises to produce something effective. I did not have such doubts for personal computers. When the first personal computers were released (kits and then Apple II), I was student in Computer Science. For me it could not be an invention because personal computers were just using the same Von Neuman design as mainframes with cheaper components. Still in one century from now people will probably remember that between 1980 and 2000 there were two key inventions, the personal computer and the Web.

There is another point: if I had seen the original CERN browser in 1991 with pictures and text on different windows I would have needed all my skills to identify the Web novelty and all my imagination to envision its future. I would have perhaps concluded that it was an invention but I would not have written that it was a big invention because Xanadu looked more promising.

We can deduce from these examples the following rules:

To identify the novel part of a proposal or patent application you need to understand the matter.

More you understand the matter, less you are able to grade an invention.

Now we can see in another way the observation that to get a legally-strong patent an applicant only needs to describe on time a combination of known processes and methods, useful and novel because of an environment change like the Web or a new regulation. Even the biggest and most useful inventions are nothing more that combinations of known processes and methods, useful and novel because of an environment change. An invention is essentially combinatorial and opportunistic.

There is another point of importance. In our brain there are no parts specialized in inventing. There are parts able to learn, to store knowledge and to retrieve or design solutions. Formally we cannot say that an invention is always a combination of old inventions. We should say that an invention is a design that represents a progress of science or useful arts, a design being a combination of knowledge items previously learnt by the inventor. Though the details of the brain implementation are not known efforts have already been made to reproduce this function in artificial intelligence. To represent design knowledge the Function, Structure, Behavior (FSB or SFB) model has been developed. Very coarsely a known design can be represented by:

Its function, the goal of the design. To represent the function in a computer program the system can use a hierarchy of sub-functions.

Its structure, the parts of the design and their relationships.

Its behaviour represented by explanation chain/graphs that model causality and temporal relationships and state-transitions diagrams.

There are a couple of documents reasonably easy to read about FSB. You can try for instance a Function -Behavior - Structure view of social situated design agents by John S. Gero and Udo Kannengiesser. Learning to be creative and the creative memory by T Zamenopoulos and K Alexiou presents a project where learning is seen as a function used to capture, maintain and restructure SBF interdependencies.

The use of function, structure and behavior in design by Marton E. Balazs & David C. Brown is an introduction to design using FSB knowledge of interest in a document about patenting. The input is the function of the object to design. This is quite similar to project requirements. Balsz and Brown note that the knowledge associated with design objects can be classified into the following types:

Structural knowledge -- knowledge about the components which comprise the object and their relations;

Behavioral knowledge -- knowledge about the behavior of the object, i.e., about ways the device responds to changes in its environment and/or in its own state;

Teleological knowledge -- knowledge about the purpose and the way the object is intended to be used;

Functional knowledge -- knowledge about how the behavior of the object is used to accomplish its intended use.

Balsz and Brown further note an essential difference between the nature of the first two and the last two types of knowledge. This difference results from the following:

For a given object both structure and behavior are objective in the sense that the former is given by the physical existence of the object, while the latter can be (objectively) determined based on physical principles.

On the other hand teleology and function of an object are subjective. The first one reflects the intention of a human (the designer or the user) in using the object. The second one (the functional knowledge) is an abstraction of the behavior by a human through recognition of the behavior in order to utilize it [Umeda & Tomiyama, 1993].

A system using a bank of designs defined in FSB can solve problems defined in function terms. If the system doesn’t find a design with the problem function it looks at sub-functions. It can also look for analogies. For the moment researchers are just able to reinvent door handles, taps and so forth. I thought about using FSB to represent existing program designs. Then it should be possible to use the design bank to create new designs also represented in FSB and even to generate dynamically patent skeletons. Frankly I do not know if this application of FSB will ever be practical. For instance representing the problem to solve is tedious, time consuming and requires more skills than traditional design.

We can see that an invention differs from a simple design by a particularly useful teleology and function (this teleology and function being subjective and ascertained by the invention users) in regard of its structure and behaviour (which are objective and represent the inventors’ work).

When inventors write patents they talk about what they know,

the structure and the behaviour of a design, which is necessarily an opportunistic combination of old inventions,

the problem they had to solve and not the problem actually solved by this invention

The patent office must determine if a patent application is patentable with the information contained in this application. In USA but not in Europe the invention success is also considered. This method is not necessarily effective. Other factors like the management and marketing skills of the application may influence the success of the invention. Furthermore software and business method patents have a deterring effect. The best illustration is maybe Smalltalk. This language had the features that eventually succeeded with Java. It allowed developing good quality and portable programs in less time. But the customers did not want a pricey single source and preferred to wait for a free industry-endorsed solution.

The patent manual may say that "non-obviousness is demonstrated by showing that practicing the invention yields surprising, unexpected results." To know these unexpected results the inventors would need to wait for others to practice the invention. So inventors would have to wait before filing the patent, so would get a later priority date. This would further imply that the invention would not be kept secret before the filing. In that respect inventors have necessarily to cope with conflicting requirements.

However this does not mean that patent offices have to accept the proprietarian model and to grant patents to all applications meeting some rules.

I’m convinced that today some companies developing software products start the patent process as soon as product requirements are known:

The first step consists in checking if a process or method satisfying these requirements may infringe a patent. This is possible because the product requirements are derived from an analysis of competing products and defined in order to minimize development risks. The requirements are defined to be implementable and therefore with a design blueprint in mind. They contain enough information for a person of the art to conduct prior art searches, raise a warning or suggest requirement changes if the envisioned product is too close to a patent.

The second step can start as soon as the product patenting has been approved and consists in writing (1) a list of references, which is basically the prior art search result (2) the abstract which is a "concise statement of the technical disclosure [...] and should include that which is new in the art to which the invention pertains" (3) the background of the invention where the drawbacks of prior art are shown and the usefulness of the invention is demonstrated (4) a first draft of the claims.

The third step starts as soon as the design is completed. It consists in writing the summary of the invention and drawing the figures.

Some requirements may require a proof of concept. In that case the fourth step starts once the results of the proofs of concept are known. Otherwise the fourth step immediately after the third step. The fourth step consists in writing the detailed description of the preferred embodiments.

The "beauty" of the system is that the patent application is filed before the beginning of the programming phase. Patent strategies being confidential this is impossible to give a percentage of patents processed in that way. My conviction is based on the following facts:

The US patent law allows filing provisional patents containing claims and drawing but no claims, and whose unique constraint is to disclose the invention subject matter. American companies frequently file regular project documents as provisional applications. In such cases there is evidence that the patent subject matter is the project and hence the product subject matter.

Some patents are made public before the announcement of the corresponding product.

Some patents have preferred embodiments that contain no technical difficulty requiring research and prototype development.

Depending on the point of view such practices may be perceived as an abuse or as the recognition that the applicant cannot appreciate if a design is only a design or if it is an invention:

An invention is as combinatorial and opportunistic as any combinatorial and opportunistic design.

An invention differs from a simple design by a good ratio (teleology + function) / (structure + behaviour) where both teleology and function are subjective and ultimately graded by users

This is known for a while. Daniel Webster who represented in a Circuit court Charles Goodyear, the inventor of the vulcanization, that was combining rubber, sulphur, lead salt and heat said:

"If Charles Goodyear did not make this discovery, who did make it? Who did make it? Why, if our learned opponent had said he should endeavor to prove that some one other than Mr. Charles Goodyear had made this discovery, that would have been very fair.

On the contrary they do not meet Charles Goodyear's claim by setting up a distinct claim of anybody else. They attempt to prove that he was not the inventor by little shreds and patches of testimony. Here a little bit of sulphur, and there a little parcel of lead; here a little degree of heat, a little hotter than would warm a man's hands, and in which a man could live for ten minutes or a quarter of an hour; and yet they never seem to come to the point. I think it is because their materials did not allow them to come to the manly assertion that somebody else did make this invention, giving to that somebody a local habitation and a name."

[I present the disputed patent (#3,633) later. I found the excerpt at http://inventors.about.com/cs/inventorsalphabet/a/rubber.htm]

To assess the innovation in a software patent I assume that the disclosed invention was made in the following way:

The inventor(s) designed something from requirements, frequently issued by Marketing for a business method, according to constraints usually technical (available tools, existing infrastructure) and cultural.

The design became the preferred embodiment.

The requirements had a goal discussed for instance in the business case. This goal was to solve a problem. This problem is obfuscated to become the problem solved by the invention.

The design can be generalized in an invention summary. The inventors can then consider other embodiments.

Claims are usually designed by lawyers to get the most from the description stuff. However lawyers meet inventors who tell them about every requirement they had. So a means designed to satisfy a requirement typically translates into a claim element.

I believe that this scenario is correct because:

Usually only the preferred embodiment is detailed and quite frequently only one embodiment is disclosed.

Quite frequently the invention summary is the summary of the preferred embodiment.

An invention developed in that way I call later "project patent" may be a good invention. In fact any invention that is not a discovery is a lucky design and to design something we need requirements to find analogies and constraints to eliminate some analogies.

However when an invention is made by the book the process is:

The inventors have an idea.

Up to the time they have a workable solution inventors repeat an iterative process which consists in designing, implementing, testing, analysing the strengths and weaknesses of the implementation.

This process seems to still be used by researchers who work with Universities and look for licence fees. In these cases constraints exist but they relate to costs, know how... and not to compatibility issues with an existing infrastructure. For instance when he designed his steam engine Watt had to deal with providers unable to deliver parts conforming to specifications and he had to adjust his design to cope with this limitation. The inventors have a goal (reviewed by their sponsors) but no requirements. Companies will license the invention only when it meets their core requirements but they will usually agree to adjust their minor requirements to be able to use it. The innovation assessment described below does not deal very well with these "research patents" but is able to detect them.

There is a third type of patent process illustrated by Lockwood and MercExchange patents. In this process the applicant analyzes an existing system (used goods and collectibles shops and auction systems in case of MercExchange, CRSs in case of Lockwood) and a new facility (low-cost WAN for MercExchange and multimedia for Lockwood). Then the applicant applies a transformation of the old system with the new facility. The applicant is typically a person working alone and looking for license fees. With this process the requirements and constraints derive from the fact that the invention must implement the functions of the old system and satisfy the same users. I call these patents "transformation patents". The innovation assessment described below work well with these patents when the person who makes the assessment knows the old system and the new facility.

There is a considerable difference in resources between the three types of patents:

Transformation patents without prototypes and tests cost few man months in investigation.

Research patents with the iterative research effort cost one to ten man years.

Projects for which patents are filed may cost hundred and more man years. Though project management aims to minimize risk and therefore opportunities for participants to exercise their ingenuity, though the main delivery of the project is a product, project patents are the public manifestation of big efforts including almost inevitably some ingenuity.

This innovation assessment starts with the analysis of the preferred embodiment, of the invention background (problem solved and drawbacks of previous solutions) and of the claims. The innovation assessment aims to extract from this stuff:

The design. The goal is to identify the invention parts, what they do and how they communicate with each other. I frequently need to also read the invention summary. Design analysis is the easiest part of the assessment because the patent normally contains this information.

The requirements. To identify the requirements I read the invention background and the claims. To confirm my guesses I frequently consult the applicant web site and press releases.

The constraints. There is no place in a patent where to express a constraint except the invention background. Furthermore because they live with these constraints inventors do not feel necessarily to explain them. To identify constraints I list design blocks and requirements. When I cannot explain a design block or an apparatus with requirements I assume that there is a constraint. It is usually impossible to name a constraint with only one patent but because all inventions from an applicant were designed with the same constraints I frequently can name constraints when I have already analyzed a couple of patents from this applicant. Constraint identification is like traditional intelligence. I frequently need to cross different pieces of information.

This work is actually easier than it looks, at least for project patents usually filed by Corporations. Corporate patenting is a corporate process. Therefore I can safely assume:

A time-constrained patenting process. Documents have to be delivered on date regardless of their state of completion.

A patenting process monitored with quantitative rather than qualitative metrics. If a person involved in the process is unable to deliver work of the needed quality it usually goes undetected.

A workflow process. Each step produces deliverables that are forwarded to the next step, which is handled by another team. A team only knows what it needs to know to do its job. For instance inventors do not monitor the patenting process and usually do not review the patent application which is filed. So an error made at one stage cannot be fixed at a later stage.

The result is therefore less than perfect, which is both good and bad:

Companies are usually unable to control their disclosures in documents of more than 5,000 words. Press releases are controlled. Patents are not.

Explanations are frequently obscure. Usually this is because someone reproduced something that she did not understand. Obscurity is per se a useful piece of information: it means that people involved in the patent process do not talk to each other. But making sense of something obscure is challenging. Here living in a country whose language is not English is an advantage: you already perfected the art of translating back from your language to English to understand a paper.

Once I have a design, a requirement list and a constraint list I can assess the innovation. When there is one requirement or constraint per design block and when design blocks are independent then no synergistic effect is possible. Some novelty and inventiveness may be present in a given design block but

Usually design block serve a purpose in a well-known manner. This is the combination of blocks that makes the invention patentable.

Because of the patent scope not enough details are usually disclosed on a design block to establish its novelty or inventiveness.

The design may be also layered. For instance a design can contain a module block per requirement and a service block per constraint. Module blocks uses service blocks but modules blocks are independent from other module blocks. Layered designs are the consequence of known analysis practices. If blocks do not communicate with each others in another way then I regard them as independent.

To illustrate this discussion we can turn our attention to something that is widely regarded as a major invention though it was not patented, the Web.

We can presume that there were two requirements:

Display hypertext documents from different sources

Handle queries

There were three constraints:

The invention had to use the IP network to get documents

The documents were stored in file systems

To handle queries the invention had to call programs

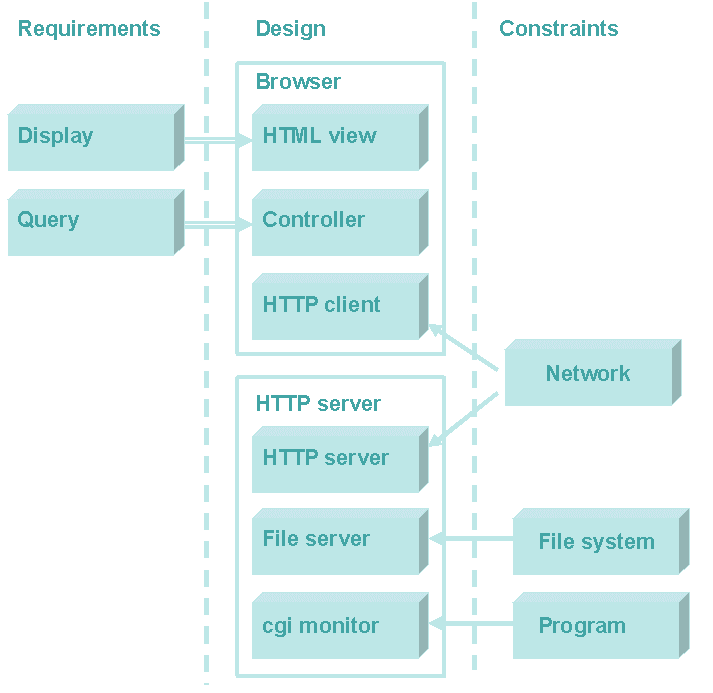

Then we can represent the original Web like this:

Because there is a network a client/server protocol, HTTP is defined. The browser contains an HTTP client block that uses this HTTP protocol to call an HTTP server block on server side. The server serves documents using a file server block and handles queries with a cgi block. The browser processes requests with a controller block and displays documents using an HTML block.

If I regard these blocks as independent because they communicate through well-defined interfaces and protocols and because the block design conforms to well-known practices in 1990 then I must conclude that the Web is a sophisticated design but not an invention. This observation may look surprising but it captures a part of the reality. There was no debate about the inventiveness of the Web in 1990 simply because the Web was born free and Open Source. Otherwise similar systems would have released and patented with different protocols and document formats. For instance, almost certainly, Adobe would have released a system displaying Display Postscript or Acrobat documents. A hypothetical Web patent would have been unable to prevent such things.

I think that the Web was an invention because of the relative simplicity of HTML and HTTP that made this invention relatively easy to implement. But if the Web had been a commercial product I would have identified the innovation only if the patent (or the applicant Web site) had disclosed details about HTTP (GET and POST requests at least) and about use of HTML tags like <A> and <FORM>.

To allow readers to safely state that this invention was novel and non obvious the patent had to claim:

The use of a text protocol (HTTP) and of a text document format (HTML)

A means to submit queries in documents

A means to represent queries and their parameters in HTTP

Such claims are not necessarily present in project patents because these claims are harder to word in a way that remains general enough to cover evolutions of the product and in transformation patents because such aspects were not necessarily explored by inventors.

In innovation assessment this is important to spend time on the first step in which we put your feet in the inventor shoes and try to reverse engineer the invention process. This is the only way we can get results of interest for business intelligence. However we only capture one dimension of the invention, its structure. Though this dimension is increasingly important, design blocks being abundant and for most of them known art, there are two other dimensions:

The objects used and produced by the invention. In case of software and business methods inventions these objects are data.

The processes of the invention. This is important to not confuse the structure and the processes. A large proportion of the design blocks exist to link the invention to the surrounding world, which is highly codified and provides many facilities. We may notice that what we called technical constraints above is the counterpart of using facilities such as networks and file systems. If the innovation consists in using facilities in a different way then it is captured by the structure analysis. If the innovation consists in using a new process with a traditional design then the innovation is captured by the process analysis.

We may notice that patents had always these three dimensions. We can consider for instance the patents of Charles Goodyear for the rubber:

240, the first patent of Goodyear (two pages, three claims) granted on June 17, 1837.

1,090 actually filed by Nathaniel Hayward, assigned to Goodyear for the use of sulphur (one page, one claim) and granted on February 24, 1839.

3,633 filed by Goodyear for the vulcanization (two pages, three claims) granted on June 15, 1844.

You still can find these patents on the USPTO site in TIFF format. You can also find 240 at http://www.todayinsci.com/G/Goodyear_Charles/GoodyearPatent240.htm. By the standard of today these patents are very short patents. They contain no figures and their claims are less formalized than in today patents (if you file a patent in the Goodyear way the US patent office will probably recommend you to hire a patent attorney.) However the three dimensions are already present. If we take the example of 3,633:

The objects used by the invention are India-rubber, sulphur, white lead and cotton. The object produced by the invention is a fabric.

The process consists in combining India-rubber, sulphur, salts of lead and heating the compound.

The structure is not apparent. However we may notice that a first design block combines the India-rubber, sulphur and white lead, a second design block makes a sandwich of the compound produced by the first block with cotton-batting, a third design block heats the compound produced by the second block. We even see that the structure comes from the facilities used by the invention and by the constraints they induce. The first block deals with chemistry. The second block deals with mechanical means and the third block deals with ovens.

In the rest of this section I focus on software and business methods inventions. Therefore objects are data and processes process data.

I check if the invention:

Represent data in a novel manner on disks, in documents and/or in protocols as illustrated by the Web example.

Distribute and access data in a novel manner. An example might be Grid architectures. For instance with the Message Passing Interface (MPI) collective operations input data are distributed to the different nodes and output data are merged. Data are submitted to programs on intermediate and end nodes.

I check if the invention:

Collect and use new data. Example: a search engine may record user queries and use these data to display advertisements corresponding to the user areas of interest.

Combines data in a novel manner.

Transforms or analyze data in a novel manner.

An innovation produces:

A known and useful result in a cheaper way. For instance since the eighties transactional systems are able to process 5,000 requests per second. Then these systems were running on mainframes and programmed in assembler. The cost of these systems limited their application to few cases. With diminishing costs it has been possible to use similar systems for applications that generate less revenue like systems that process cell phone messages and mails.

More of a known and useful result for a given cost. For instance online reservation systems offer a low fare search facility whose implementation is resource consuming. In 1999 processing 20 low fare search requests per second was a good result. Today online reservation systems can process far more requests.

A useful result that was not obtained before. In this case more desirable was the result, biggest is the innovation.

It is possible to assess the two first types of innovation, which are improvements. This is a demanding task because we need to know the existing solutions at a level of detail sufficient to evaluate the differences between the invention and the prior art. Usually it is not possible to reproduce the invention and to check if the benefits claimed by the invention are real. But we can find if an invention MAY be an innovation or if the invention is PROBABLY not an innovation.

The third type of innovation is harder to assess.

The easiest case is the case where the desirability of the invention is already established. For instance if an invention discloses a voice recognition system that does not require training and is reliable at 100%, this invention yields a highly desirable result and we can safely say that this invention is a big innovation. The problem is that such things happen almost only in literature and movies. The only examples in computer field that comes to mind are Smalltalk and the Apple Mac Intosh. I discussed Smalltalk above and the Mac Intosh is not so strong from a legal point of view. It came after another computer of Apple, the Lisa, which came after numerous findings in the Xerox PARC. So this innovation had many contributors.

A second case is the case in which the goal and the target (customers...) of the invention are well established. For instance if the competitor Web site refers to the invention with a "patent pending" notice or if the financial report of the competitor explains what is expected from the invention we have a serious work basis. We can identify the market impacted by the invention and evaluate the competitive advantage that the applicant can expect from the invention.

The third case is the case where neither the desirability nor the actual goal and target of the invention can be established by external means. When the only source of information is the invention itself we are in the same situation as the inventors and the patent office. As we have seen above we cannot guess how the invention will eventually be used. We can get a first idea of the invention result and usefulness from reading the title, abstract and background section of the patent. For instance the abstract of the Eolas patent (5,838,906) starts with:

"A system allowing a user of a browser program on a computer connected to an open distributed hypermedia system to access and execute an embedded program object. The program object is embedded into a hypermedia document much like data objects. The user may select the program object from the screen. Once selected the program object executes on the user's (client) computer or may execute on a remote server or additional remote computers in a distributed processing arrangement. After launching the program object, the user is able to interact with the object as the invention provides for ongoing interprocess communication between the application object (program) and the browser program."

This is an acceptable definition of an applet or of an ActiveX control. From the abstract and the lengthy background the reader can easily deduct that this patent produces a useful result. [The fact that 5,838,906 is novel and not obvious has yet to be confirmed in court but this is not the subject of this section.]

In 5,838,906 the result is the capability in the context of client/server programming to run the client in a browser page. This result almost confuses with the means, which is to embed a client object in the page. The result and the means may also be quite distinct. For instance the abstract of 5,845,265 contains:

"The present invention relates to used and collectible goods offered for sale by an electronic network of consignment stores. More specifically, the present invention may be an electronic 'market maker' for collectable and used goods, a means for electronic 'presentment' of goods for sale, and an electronic agent to search the network for hard to find goods. In a second embodiment to the present invention, a low cost posting terminal allows the virtual presentment of goods to market and establishes a two tiered market of retail and wholesale sales."

The result is a "market of retail and wholesale sales" and the means is "an electronic network of consignment stores selling used and collectible goods". 5,845,265 is a MercExchange patent that I present in more details below. For infringing this patent eBay and Half.com were ordered to pay MercExchange $29.5 million in damages. eBay establishes a market of retail sales but is certainly not an electronic network of consignment stores selling used and collectible goods.

We must consider both the result and the means. Otherwise the assessment of inventions achieving novel results would not be consistent with the assessment of improvement inventions, in which we only consider the means, the result being not novel. In case of 5,845,265 we necessarily conclude that:

The result (a market of retail and wholesale sales) is highly desirable

The means is not practical

5,845,265 is not practical because it requires a program to be installed in or on behalf of consignment stores and:

Consignment stores are frequently small organizations for which the cost of purchasing and operating a new program is a significant burden. In other words they will certainly buy the program (they already run programs) but only if the market evolves in such a way that they have to.

Therefore 5,845,265 faces the chicken and eggs problem. For the program to sell the program has to be already installed in many consignment stores. For the first adopter the program is not better than a Web site.

In this section I examine how techniques used in innovation assessment could be applied also to decide about the patentability of an invention. I discuss claims, the doctrine of equivalents and the non obviousness test (the inventive step).

I have showed that

An invention is always a combination of prior art

Inventors choose the prior art and combine this prior art using one process among corporate project, transformation analysis and research program. All these processes can be reverse-engineered using the Design-Requirement-Constraint (DRC) analysis exposed in the first step of the innovation analysis.

The DRC analysis helps:

To clarify the subject matter of an invention

To check if the description sufficiently supports the invention claims

To identify cases where the combination of prior art produces no synergistic effects or, to say it in another way, cases where the whole invention does not produce more results than the sum of its components, cases in which the invention should not be patentable.

To identify cases where an invention is only a transformation and this transformation (combination of known art with new means) is obvious, other cases in which the invention should not be patentable.

This analysis should be combined with an analysis of the objects (data in case of software and business method patents) used and produced by the invention and with an analysis of the invention processes.

The scope of a patent is determined by the claims only. The description serves three purposes:

The description must support the claims. The lack of an adequate description makes a claim invalid.

The exclusive right granted to the inventor has a counterpart, which is the disclosure of the invention. The description must explain the invention in order to enable persons of the art to reproduce the invention once the patent has expired.

The description can be used by the examiner and the court to clarify the meaning of words used in claims [claim construction].

Claims are not easy to interpret even for examiners and courts (see the Markman hearing later in this page). Claim analysis is a time-consuming and demanding task especially when a patent has hundred and more of them as it is frequently the case in USA. Only the richest companies can make a thorough analysis. The question could be raised whether or not there is willful infringement in such context. Let’s consider the following situation:

A company X files a patent in 2000.

A company Y uses the process of the company X patent, two months after the company X has filed the patent. Then company Y has twenty employees and calls a lawyer only to check contracts.

The company Y is very successful. In 2004 everybody knows about this company, which now has a legal department and files patents.

The same year a patent is eventually granted to company X, which immediately sues company Y.

This situation is more or less what happened to eBay a couple of years earlier. There is a limit to the due diligence that can be expected from a small company. In the situation above company Y had probably the resources to identify the company X patent in 2002 and to make a thorough analysis in 2003. In this case the court should logically find a willful infringement only for 2003 and 2004. There is another issue. The founder of Y got money from investors two months before company X filed its patent. When it is sued company Y has to postpone its IPO. Investors will get back less money and later. Because startup business is less profitable investors invest less in new companies. We can see that the complexity of the patent analysis combined with the growing number of filed patents favors incumbent companies able to cope with the risks associated with their size and make harder the creation and the growth of new entrants.

Today the abstract has to be consistent with the rest of the specification and is used to classify the invention. But though it is the first part of the invention the abstract does not contribute to the scope determination. The simplest solution to the problem exposed above would be to state that the scope of a patent is also determined by the abstract. Obviously the doctrine of equivalents would have then to apply to the abstract like it applies today to the claims.

An abstract has a definition as precise as the claim definition. In USA "a patent abstract is a concise statement of the technical disclosure of the patent and should include that which is new in the art to which the invention pertains. If the patent is of basic nature, the entire technical disclosure may be new in the art and the abstract should be directed to the entire disclosure. If the patent is in the nature of an improvement in an old apparatus, process, product or composition, the abstract should include the technical disclosure of the improvement. [...] If the new disclosure involves modifications or alternatives, the abstract should mention by way of example the preferred modification or alternative.

The abstract should not refer to purported merits or speculative applications of the invention and should not compare the invention with the prior art.

Where applicable, the abstract should include the following:

if a machine or apparatus, its organization and operation;

if an article, its method of making;

if a chemical compound, its identity and use;

if a mixture, its ingredients;

if a process, the steps."

The relationship between claims and specification is not the same as the relationship between the abstract and the specification. The specification is only required to support claims (provide an adequate description) whereas the abstract is a statement of the technical disclosure. So including the abstract in the scope determination would be a very important change. This change would make patent law closer to copyright law (the law would protect against copies of the disclosure in the way defined by claims).

Another solution may be to reduce the number of claims. This is the solution adopted by the EPO to facilitate the examiner job.

The Article 82 of the European law (EPC) is:

The European patent application shall relate to one invention only or to a group of inventions so linked as to form a single general inventive concept.

This principle is usually called Unity of Invention.

The Article 84 of the European law (EPC) is:

The claims shall define the matter for which protection is sought. They shall be clear and concise and be supported by the description.

Its interpretation is clarified by the Rule 29 that defines the form and content of claims:

(1) The claims shall define the matter for which protection is sought in terms of the technical features of the invention. Wherever appropriate claims shall contain:

(a) a statement indicating the designation of the subject-matter of the invention and those technical features which are necessary for the definition of the claimed subject-matter but which, in combination, are part of the prior art;

(b) a characterising portion - preceded by the expression "characterised in that" or "characterised by" - stating the technical features which, in combination with the features stated in sub-paragraph (a), it is desired to protect.

(2) Without prejudice to Article 82, a European patent application may contain more than one independent claim in the same category (product, process, apparatus or use) only if the subject-matter of the application involves one of the following:

(a) a plurality of inter-related products;

(b) different uses of a product or apparatus;

(c) alternative solutions to a particular problem, where it is not appropriate to cover these alternatives by a single claim.

(3) Any claim stating the essential features of an invention may be followed by one or more claims concerning particular embodiments of that invention.

(4) Any claim which includes all the features of any other claim (dependent claim) shall contain, if possible at the beginning, a reference to the other claim and then state the additional features which it is desired to protect. A dependent claim shall also be admissible where the claim it directly refers to is itself a dependent claim. All dependent claims referring back to a single previous claim, and all dependent claims referring back to several previous claims, shall be grouped together to the extent and in the most appropriate way possible.

(5) The number of the claims shall be reasonable in consideration of the nature of the invention claimed. If there are several claims, they shall be numbered consecutively in Arabic numerals.

(6) Claims shall not, except where absolutely necessary, rely, in respect of the technical features of the invention, on references to the description or drawings. In particular, they shall not rely on such references as: "as described in part ... of the description", or "as illustrated in figure ... of the drawings".

(7) If the European patent application contains drawings, the technical features mentioned in the claims shall preferably, if the intelligibility of the claim can thereby be increased, be followed by reference signs relating to these features and placed between parentheses. These reference signs shall not be construed as limiting the claim.

The most important topic is topic 2 that says that a European patent application should normally contain only one independent claim per category, the categories being product, process, apparatus and use. This means in practice that a European patent application usually contains only one independent claim. The topic 5 further says that the number of the claims shall be reasonable in consideration of the nature of the invention claimed. The topic 6 clarifies the principle of Article 84 that the claims completely define the matter for which protection is sought ("claims shall not rely on references to the description or drawings"). It is needed because topic 7 allows and recommends referring to the description in the claims.

The Unity of Invention also exists for International stage applications and in USA.

To get a patent in many countries the preferred means is to first file an application in the national patent office and then to file an international application, based on this application, and designating the other countries where the inventor wants to also get a patent. The main deliverable of the international stage is a prior art international search report. A prerequisite to the international search is a weaker Unity of Invention, described in one section of Chapter 37 of the Code of Federal Regulations, 37 C.F.R. 1.475 ("Unity of invention before the International Searching Authority, the International Preliminary Examining Authority and during the national stage"). This section says:

"An international and a national stage application shall relate to one invention only or to a group of inventions so linked as to form a single general inventive concept ('requirement of unity of invention'). Where a group of inventions is claimed in an application, the requirement of unity of invention shall be fulfilled only when there is a technical relationship among those inventions involving one or more of the same or corresponding special technical features. The expression 'special technical features' shall mean those technical features that define a contribution which each of the claimed inventions, considered as a whole, makes over the prior art."

For USA the Unity of Invention is defined in 37 C.F.R. 1.141 ("Different inventions in one national application") that says:

"Two or more independent and distinct inventions may not be claimed in one national application, except that more than one species of an invention, not to exceed a reasonable number, may be specifically claimed in different claims in one national application, provided the application also includes an allowable claim generic to all the claimed species and all the claims to species in excess of one are written in dependent form (1.75) or otherwise include all the limitations of the generic claim."

The European articles and rule have the following strong points:

A European application usually has between ten and thirty claims when the US application frequently has hundred and more claims.

A European application usually has one independent claim when the US application usually has half a dozen independent claims, most of them being rewordings of the first independent claim. With US applications, instead of focusing on the question "do we have a process similar to the process presented in this independent claim?", patent analysts spend time checking the differences between the independent claims.

As we have seen applicants who have filed a patent application in a first country can file an international application designating other countries. Thank to the international treaties these applicant keep the benefit of the filing date in the first country in other countries as far as they do not substantially change the patent specification. For the claims this is another story because the law and the prior art can be different, and - this is what requires the biggest effort - because the form and content of claims depends on the country. This has two consequences:

Extra expenses even if anyway getting a patent in several countries cannot be cheap, notably because translations in local language are frequently compulsory.

The applicants themselves do not know exactly the protection they have been granted.

The drawbacks of the current model are so apparent that the USPTO seems to have considered adopting the European Unity of Invention as explained in European Patent Office Implementation of Unity of Invention and Strategic Concerns of U.S. Practitioners for Proposed U.S. Restriction Reform Options

by Kevin J. Dunleavy, Esq. Knoble & Yoshida, LLC.

Doctrine of equivalents is (relatively) self-explanatory. It says that using essentially the same means to achieve essentially the same result is counterfeiting. A court wrote "mere colorable differences, or slight improvements, cannot shake the right of the original inventor." Doctrine of equivalents should not be confused with the obviousness test (discussed in the next section.) The doctrine of equivalents aims to widen the exclusive right granted to a patent whereas the obviousness test aims to prevent patenting minor improvements that people of the art would have made if they had faced the same problem as the inventor (there must be a minimal inventive step between the prior art and a patent application.)

To illustrate the difficulties raised by the doctrine of equivalents we can take the example of the first claim of 5,845,265 reproduced below in extenso. This claim describes a system using bar codes. Doctrine of equivalents makes impossible to patent, sell or use a system that would differ from 5,845,265 by the use of RFID tags instead of bar codes. However the claim presents a system comprising a digital image means for creating a digital image of a good for sale AND a bar code scanner. We could fully agree on a loose interpretation of bar code scanner like "means to identify the good" if the system comprised a scanner or a digital camera. But the system has a digital image means for creating a digital image of a good. Therefore we can assume that the author wrote bar code on purpose. If we do so then a system whose sole difference with 5,845,265 is the use of another means for identifying the good can be patented, sold or used. But this is not so simple. In the MercExchange v. eBay case we analyze below we learn that for the inventor "digital image means for creating a digital image of a good" could also be an image repository.

A direct consequence of such interpretation problems is that claims are worded with the most general expressions and overuse the word "means". Instead of using truck a claim will use "transportation means". Instead of using nail a claim will use "fastening means". This makes claims unnecessarily obscure and of claim reading a kind of crossword. [And when general expressions do not exist (which is common for inventions in metallurgy, ceramics, pharmacy, pharmacology and biology but not for business methods) inventors use Markush groups where they cite lists of multiple items, anyone of which can be used in part of an invention. To spot a Markush group look for phrases like "selected from the group consisting of".]

We can now turn our attention to prosecution history estoppel that I present in the patent search page. Generally speaking, if someone states that something is so and, in reliance upon that statement, another person acts in a particular way, possibly to her detriment, then the person who made the statement is prevented, or estopped, from denying the correctness of the statement which she originally made. During the patent prosecution an examiner checks the claim novelty. When the examiner objects to a claim the applicant usually amends this claim. If the examiner finds no more objections to the amended version of the claims the patent is granted. If the patentee (the former applicant) could use the doctrine of equivalents for an amended claim it would deny in some way the correctness of the amendment that allowed the examiner to grant the patent.

The consequence is that the doctrine of equivalents widens the patent scope in a way that cannot be deduced from the patent reading. To see if a claim can get the benefit of the doctrine of equivalents we must also read the documents of the patent prosecution. When we find that the examiner objected to a claim we must appreciate the objection and the claim amendment. If the applicants had to be more specific on one phrase then they are estopped on this phrase, which means that a process or system that only differs from the patent by this phrase does not infringe the patent.

On November 29, 2000 the United States Court of Appeals Court tried to put in place a more workable rule. In this Festo ruling the United States Court of Appeals Court held; (1) Any reason for amendment to a patent claim that is related to patentability will give rise to prosecution history estoppel; and (2) When the amendment creates a prosecution history estoppel, there is no range of equivalents available for the amended elements. But then to minimize the exposure to estoppel some attorneys increased the number of claims, the idea being that with so many claims with slightly different wording only a low percentage of claims would be estopped and therefore the patent should be given the expected scope. Instead of amending claims these attorneys replaced rejected claims with new ones. Were these attorneys trying to fool the courts, the competitors (that could feel that they infringed when they did not) or their customers? Anyway on May 28, 2002 the Supreme Court vacated the Festo decision. As reported here the Supreme Court disagreed with the complete bar rule set out by the Federal Circuit, preferring instead a flexible approach to the doctrine of equivalents, so on the approach used before Festo.

Therefore to properly assess the scope of a patent a potential infringer must:

check the examiner rejections and the inventor answers and amendments in the patent’s prosecution history available online in Europe (Online file inspection) and in USA (Patent Application Information Retrieval (PAIR)),

properly interpret the nature of these rejections, answers and amendments,

appreciate how claims are estopped by rejections, answers and amendments.

The prosecution history of a patent typically contain two rejections and as many answers and amendments. All these documents are files of about ten pages. So the analysis of a patent scope takes time and yields uncertain results.

Obviousness is defined for USA patents by 35 USC 103 "Conditions for patentability; non-obvious subject matter" that says:

"A patent may not be obtained though the invention is not identically disclosed or described as set forth in section 102 of this title, if the differences between the subject matter sought to be patented and the prior art are such that the subject matter as a whole would have been obvious at the time the invention was made to a person having ordinary skill in the art to which said subject matter pertains. Patentability shall not be negatived by the manner in which the invention was made."

Most readers of the MercExchange patent discussed below, 5,845,265 would probably conclude that if the differences between the subject matter sought to be patented ("A system for presenting a data record of a good for sale to a market for goods, said market for goods having an interface to a wide area communication network for presenting and offering goods for sale to a purchaser, a payment clearing means for processing a purchase request from said purchaser, a database means for storing and tracking said data record of said good for sale, a communications means for communicating with said system to accept said data record of said good and a payment means for transferring funds to a user of said system..." [claim 1]) and the prior art made of:

Means to provide an inexpensive online service (Internet, Web servers, X25, cheap servers using PC components...)

Consignment shops

Traditional auctioning

are such that the subject matter as a whole would have been obvious at the time the invention was made to a person having ordinary skill in the art to which said subject matter pertains, the person of ordinary skill in the art being in 1995 a analyst who knows means to provide an inexpensive online service and is assigned the task of implement electronically with these means the consignment shop and auctioning processes.

However the obviousness found by readers does not stand from a legal point of view. Obviousness must be decided by a uniform and definite test. Furthermore in obviousness assessment the emphasis has to be one of inquiry and not of quality. Innovation assessment may help to determine the scope and content of the prior art, ascertain the differences between the prior art and the claims at issue and resolve the level of ordinary skill in the pertinent art as commanded by §103. But a patent cannot be granted under the condition that it discloses something valuable, quality being a matter of opinion. On the other hand the differences between the prior art and the claims as well as the level of ordinary skill in the pertinent art can only be appreciated. Therefore I believe that someone needs first to form his opinion and then consciously take a step back to remove quality from the picture.

§103 is clarified by a case law, Graham vs John Deere Co in 1966. The dispute was about a plow effective in rocky or glacial soils. The patent described an apparatus permitting plow shanks to be pushed upward when they hit obstructions. The court first observed that "a number of spring-hinge-shank combinations are clamped to a plow frame, forming a set of ground-working chisels capable of withstanding the shock of rocks and other obstructions in the soil without breaking the shanks" and that "the prior art as a whole in one form or another contains all of the mechanical elements of the parent." Then the court identified two differences between the patent and the closest prior art and found that the essential difference between the patent and prior art results was that the patent allowed the shank to flex under stress for its entire length. The testimony of petitioners' experts showed that the flexing advantages flowing from the patent arrangement were not, in fact, a significant feature in the patent and the court further found that "certainly a person having ordinary skill in the prior art, given the fact that the flex in the shank could be utilized more effectively if allowed to run the entire length of the shank, would immediately see that the thing to do was what the inventor did, i. e., invert the shank and the hinge plate."

The court gave the following demonstration: "Even though the position of the shank and hinge plate appears reversed in the closest prior art, the mechanical operation is identical. The shank there pivots about the underside of the stirrup, which in closest prior art is above the shank. In other words, the stirrup in closest prior art serves exactly the same function as the heel of the hinge plate in the patent. The mere shifting of the wear point to the heel of the patent hinge plate from the stirrup of closest prior art - itself a part of the hinge plate - presents no operative mechanical distinctions, much less non-obvious differences."

To say it in another way obviousness is shown if a person with ordinary skill in the art would (not could) have made the invention, given the prior art, the need and the knowledge of a person with ordinary skill in the art. So to safely state that 5,845,265 is obvious we have to conclude that the person of ordinary skill in the art knowing means to provide an inexpensive online service and assigned the task of implement the consignment shop and auctioning processes with these means would have necessarily implemented a "system for presenting a data record of a good for sale to a market for goods, said market for goods having an interface to a wide area communication network for presenting and offering goods for sale to a purchaser, a payment clearing means for processing a purchase request from said purchaser, a database means for storing and tracking said data record of said good for sale, a communications means for communicating with said system to accept said data record of said good and a payment means for transferring funds to a user of said system..."

We necessarily answer no if we consider the rest of the patent and especially the cases where 5,845,265 errs, notably:

the background, which presents an electronic network of consignment stores acting as an electronic "market maker" for collectable and used goods and allowing an electronic "presentment" of goods for sale.

the abstract "A method and apparatus for creating a computerized market for used and collectible goods by use of a plurality of low cost posting terminals and a market maker computer in a legal framework that establishes a bailee relationship and consignment contract with a purchaser of a good at the market maker computer that allows the purchaser to change the price of the good once the purchaser has purchased the good thereby to allow the purchaser to speculate on the price of collectibles in an electronic market for used goods while assuring the safe and trusted physical possession of a good with a vetted bailee."

Every person of the art would not have made exactly the same choices. To my knowledge none of the companies that paid a fee to MercExchange have implemented an electronic network of consignment stores or a framework that establishes a bailee relationship and consignment contract with a purchaser of a good at the market maker computer that allows the purchaser to change the price of the good once the purchaser has purchased the good thereby to allow the purchaser to speculate on the price of collectibles in an electronic market. I explained in the third step of innovation assessment that a patent analyst would have concluded in 1995 that though the result of the invention was useful the means (network of consignment stores) was not practical.

Because the background and the abstract cannot be considered as a preferred embodiment and because they are consistent with the summary of the invention I think that the claims of 5,845,265 are an improper generalization of the description subject matter and that the scope of 5,845,265 is the consequence of two distinct pieces of work:

The work of designing a combination of prior art, means to provide an inexpensive online service (Internet, Web servers, X25, cheap servers using PC components...), consignment shops and traditional auctioning

The claim writing

The obviousness test says that if a person of the art would have made the invention then the invention is obvious. If the invention was obvious the person of the art would not have filed a patent. Therefore the subject matter that should be considered in the obviousness test has to be the subject matter following from the description and not the subject matter following from the claims.

Therefore the subject matter of the claims should be the same as or narrower than the subject matter of the description. Otherwise things can be unmanageable. This is fair and relatively easy to compare the claims of a patent application to the claims of older patents. For prior art, which is not patent applications but publications and presentations this is another story. What is published compares most of the time to a preferred embodiment and the question that the examiner and court can answer is:

"Can this preferred embodiment be regarded as a specialization of the summary of the invention?"

This is already difficult to answer this question but when claims are improperly supported by the description the question becomes

"How far the publication or presentation author would have gone in her claims if she had chosen to file a patent at the time she published or made a presentation?"

No examiner and no court can answer such a question in a uniform and definite way.

To check if the subject matter of the claims is the same as the subject matter of the description we can use the same test as the court that ruled the Morse patent and particularly its eighth claim. We already discussed this claim when we talk about USA business methods. We reproduce it again: "I do not propose to limit myself to the specific machinery, or parts of machinery, described in the foregoing specifications and claims; the essence of my invention being the use of the motive power of the electric or galvanic current, which I call electro-magnetism, however developed, for making or printing intelligible characters, letters, or signs, at any distances, being a new application of that power, of which I claim to be the first inventor or discovered." The court found that "Professor Morse has not discovered, that the electric or galvanic current will always print at a distance, no matter what may be the form of the machinery or mechanical contrivances through which it passes. You may use electro-magnetism as a motive power, and yet not produce the described effect, that is, print at a distance intelligible marks or signs. To produce that effect, it must be combined with, and passed through, and operate upon, certain complicated and delicate machinery, adjusted and arranged upon philosophical principles, and prepared by the highest mechanical skill."

In the same way the description of 5,845,265 does not demonstrate that "A system for presenting a data record of a good for sale to a market for goods, said market for goods having an interface to a wide area communication network for presenting and offering goods for sale to a purchaser, a payment clearing means for processing a purchase request from said purchaser, a database means for storing and tracking said data record of said good for sale, a communications means for communicating with said system to accept said data record of said good and a payment means for transferring funds to a user of said system..." is sufficient for establishing an electronic market. To the opposite of the eighth claim of Morse this claim is probably true (any system that includes the mentioned features above probably establishes an electronic market) but the description fails to demonstrate this fact. For instance 5,845,265 is titled "Consignment nodes" and consignment is one of the most frequent words of the specification, except in the claims where it is NEVER present.

Regarding obviousness you may also read Assessment of Inventive Step or Obviousness in the United States, Europe, and Japan by Katsuya Saito and Rosemary Sweeney.

Patent applications should conform to the Unity of Invention principle, which means that (1) a patent application should contain only one independent claim per category, the categories being product, process, apparatus and use (2) dependent claims should concern particular embodiments of that invention.

Documents of the patent prosecution should be freely available online anywhere.

Claims should have a scope smaller than or identical to the summary of the invention.

The abstract and the background of the invention should present the invention in a way consistent with the summary in such a way a person of the art that is not a patent specialist, could get a first, non-misleading idea of the invention just by reading the abstract and the background.

Patents Presentation Search Issues Strategies Business Methods Patentability Analysis MercExchange eBay Trial Reexamination Business view Granted patents Examination USPTO EPO PanIP Eolas 1-click family 1-click analysis 1-click prior art Trademark Copyright

Contact:support@pagebox.net

©2001-2005 Alexis Grandemange

Last modified